HBO Max has recently made Hayao Miyazaki’s animated films at Ghibli studios available to stream. Often called the “Pixar of Japan,” Studio Ghibli gained traction in the United States after Walt Disney produced English dubbed versions of Miyazaki’s work. Some of the more famous and recognizable films, like Spirited Away (2001) and My Neighbor Totoro (1988) may be familiar to you.

You may be surprised to find HBO Max actually has 10 Miyazaki films available for viewing. If you’re intrigued by beautiful animation and themes about the dangers of industry and coming of age, I encourage you to check some of his works out. In a two-part review series, I’ll be going through a chronological journey of Miyazaki’s famous films to see what can be learned from the experience.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Nausicaä is an adaptation of Miyazaki’s manga of the same name. Taking inspiration from a range of classic sci-fi, Nausicaä is the perfect primer for the strengths and flaws of Miyazaki’s works.

The story takes us into a world where the last remnants of humanity are struggling to survive after an apocalyptic war. Around them, a toxic jungle filled with dangerous mutated insects threatens everyday survival. The story follows the princess of a small village who wishes to understand rather than fight nature. However, her simple life is complicated when a large aircraft from a larger settlement of humans suddenly crashes down in her village’s valley.

I consider this film to be one of the most inspirational pieces of Miyazaki’s works. This movie is bursting with passion; the incredibly detailed backdrops and beautifully animated action sequences show just how talented the Ghibli team is. It’s a hero’s journey story at the heart and the sense of movement through the vibrant world is fantastic. And the worldbuilding! The world of this story is so different and incredibly ambitious, perfectly introducing our world to what Miyazaki’s world looks like.

But this film is also very flawed.

This film is filled with unnecessary information about side characters and the world around them. Nausicaä is supposed to be going through a traditional hero’s journey story: Her normal life is uprooted early on, she has to leave home, and eventually return with new information after many trials and tribulations. However, this film often reminds me more of some of the early works of Sergei Eisenstein, who made “mass dramas” where a large group of workers would be the main character of the film, running from one place to the next. Having no sense of individuality is the very antithesis of a hero’s journey story that’s trying to show the impact of an individual.

But, just like its titular character, the film is full of earnest passion and untamed skill. I encourage any aspiring filmmaker daunted by some of the masterfully crafted later works of Miyazaki to go back and watch this film. It’s evidence that everyone has to start somewhere.

Castle in the Sky (1986)

Castle in the Sky is, unlike the previous film, a story that is aimed at a much younger audience. The story follows Sheeta, a young girl who is saved by a mysterious crystal passed down by her family after she’s thrown from an airship following a pirate attack. She meets Pazu, a young boy working in a mining town, and the two go on an adventure to find Laputa, a mythical floating city related to Sheeta’s crystal.

I had consistent fun throughout the story. It’s much more character-focused, showing the journey of Sheeta and Pazu and how their relationship develops. Pazu’s father claimed to have seen Laputa but was ridiculed for years, as no one believed him. Pazu made it his life’s work to save up enough money to continue the search. Sheeta was kidnapped from her simple life in the mountains by the government agent Muska, who is searching for Laputa. What she doesn’t know is that Laputa was once the capital of a great empire and she is its heir.

While Miyazaki set up these characters to be quite interesting initially, their characters aren’t ultimately paid off. Pazu struggles with the fear of being ridiculed in the same way his father was. About halfway through the film, the government captures Sheeta and forces her to tell Pazu to go home. Pazu’s greatest fear is realized at this moment: he has to return to his normal life after failing to find Laputa. However, rather than overcoming his fears on his own, Pazu returns home to find the pirates have broken into his home and he begs to join them. While this gets Pazu back on the trail, I would’ve liked Pazu to find the strength to carry on from within, rather than from circumstance. As for Sheeta, it too often felt like she was just along for the ride. As the secret heir to the empire of Laputa, I would’ve expected Sheeta to show her strength and ability as a leader, making sacrifices and decisions for others that foreshadow the ultimate reveal.

But, ultimately, the film works for how simple it is. It’s about how evil people don’t deserve power and to believe in and trust your loved ones. Sometimes, a film only needs to be a fun adventure.

My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

My Neighbor Totoro is the most explicitly “made for kids” film out of all of Miyazaki’s works. It’s the story of a young family that moves to a new home in order to be closer to where their mother is hospitalized. The two sisters befriend a forest spirit and they go on various misadventures.

Alright, so not a lot happens in Totoro. It’s a whimsical adventure that emphasizes its plush, lovable forest creatures and the goofy physical comedy related to them. That said, there’s something about the world that Totoro paints — indeed, that’s exactly what it feels like: a painting. In Totoro’s world, people and nature live in perfect harmony where both seek to help each other when planned. With so many of Miyazaki’s works being about humanity and nature in dire conflict, it’s interesting to see his take on a world where both can live in harmony.

It’s a beautiful place.

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

This is the story of Kiki, a young witch who has to leave her hometown and find a new place to live and help people out as part of her training. Wanting to impress other witches and her family, she goes to a very large city and quickly finds herself overwhelmed. However, a friendly baker takes her in and Kiki begins a delivery service on her magic broomstick across the city.

Kiki’s Delivery Service is interesting because I went into it expecting another Totoro-like film. However, this story is much more of a coming-of-age film for young adults, with Kiki setting out into the world for the first time. Because of the theme of how cruel the world can seem to someone just setting out on their own, the plethora of side characters works much better. Much of this story is a series of vignettes: characters with motivations and desires of their own that Kiki has to learn to navigate. Kiki also has to overcome her own naivete and insecurities that any other young adult is no doubt struggling with. It’s heartfelt, in that Kiki just wants to have a place in the world, and she’s more sympathetic and realistic than any character in the previous entry.

The plot is a tad weak, with much of the second act spent meandering around, but unlike Totoro, it’s unified by a much stronger theme and character arc that works quite well.

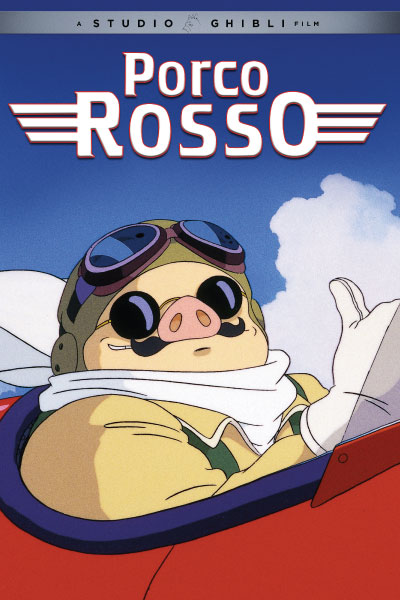

Porco Rosso (1992)

Porco Rosso is the first film in this collection that I hadn’t previously seen. It takes place in the 1930s and follows a World War 1 pilot that’s cursed to look like a pig. Although he spends his days hunting down pirates in the Mediterranean, Rosso soon meets his American rival that constantly challenges him in the air. Rosso meets a young mechanic named Fio who helps restore some of his faith in the world.

Porco Rosso is an outlier in most of the work we’ve seen so far. It takes place in the real world, with the only fantastical element being Rosso’s pig curse, and focuses on the theme of survivor’s guilt. Rosso’s squadron was shot down in the war and he was the lone survivor — what he believes to be pure luck. He feels some amount of affection toward Gina, the widow of one of his dead friends, but is scared to explore those emotions. Having been a rampant womanizer as a young man, Rosso feels like a pig and, therefore, becomes one. Rosso subtly struggles with his image: constantly wearing glasses, maintaining a very prim image, and trying to stay aesthetically pleasing. The irony of his condition, of course, is that Rosso’s rival who turns out to be an even bigger pig; confessing his love to any woman he meets.

Porco Rosso is mostly a comedy, with the main character’s dry humor (with Michael Keaton’s fitting voice) contrasting with the somewhat goofy surrounding world. Fio is an apt counterpart to Rosso’s nihilism and by the end of the story, Rosso is sacrificing his appearance in a drawn-out fistfight with his rival.

It’s a sweet film that isn’t particularly gripping, but nonetheless entertaining. With a somewhat ambiguous ending. Everything doesn’t turn out completely alright and we never truly know if Rosso returned to Gina.

And so that brings us to the first half of Miyazaki’s Ghibli. What I’ve seen so far is beautiful settings, intriguing characters, and fantastic worlds, but it hasn’t quite all felt in sync yet. Many of the plots in these films are rather flimsy, with not much of the trials and tribulations challenging the characters on a deeper level. The worldbuilding has been a lot of telling, but not quite as much showing. Every entry has been an improvement, however, and it’s astonishing to see how quickly the structures of the story improve.

We’ll be going into the later works of Miyazaki in part two next week, and I look forward to seeing the ways in which the stories improve.