In the middle of a desert, a military helicopter creates a stunning show while initiating an impossible static electrical discharge, spectacular phenomenon for all the lucky viewers of PDF.

Luckily someone had a camera, and probably, a permission to take photos of this amazing light show, so that we may enjoy this as well.

u(Image © Michael Yon)

This is what exactly happens

Helicopter RRPM is pretty much constant through out whether it be airborne or on the deck*

When the aircraft is coming in to land/slowing down and is near to the ground, it tends to have a larger vertical downward component of air (induced flow) coming through the top of the disc being pushed out through the bottom (easily seen when landing in dust or sand). As the aircraft gets near to the ground, air is sucked up all around the aircraft (recirculation). In sandy or dusty areas, this too is sucked up around and then dragged back down through the disc. Most modern helicopter rotor blades are of a composite construction but usually tend to have a stainless steel or similar leading edge abrasion strip to help prevent wear to that part of the blade. The tip of the blade has the highest velocity and would tend to have the most amount of shit hitting it. Some theories suggest scintillation is caused by certain types of sand or dust (types with a higher ore or metallic content) striking the leading edge.

One reason why you dont tend to see scintillation when an aircraft has landed is because even though the RRPM is pretty much still the same, we have no induced flow coming in through the top of the disc dragging or sucking the air (and any particles) in.

As well as making the aircraft more visible to the enemy, there are issues of this bright glow around the disc affecting NVG (partially shutting them down at a fairly critical stage of flight!)

*Modern governed engines are designed to maintain a constant RRPM at pretty much all pitch/power settings. Of course, there will be static and transient droop. Static droop is a factor of applying pitch (therefore drag) when about to take off and the nominal RRPM at flight idle** reduces. It then settles to a slightly lower RPM. This RPM is known as the Flight Governed NR. Another type of static droop is when the pitch and drag applied to the blades is too great for the engines to supply enough power and thus, the RPM reduces. Transient droop is the reduction in RRPM following a sudden large power change. For example, if one is in autorotation and the collective is raised quickly. The engines and governors cant react quickly enough to provide fuel and power so the RRPM reduces until they ‘catch up’. With modern FADEC engines, static droop is almost eliminated. An example of static droop; Sat on the ground at MPOG (minimum pitch on ground), you have a RRPM of 100% and a torque of 30%. As you apply power, the torque increases (as does pitch and drag) and the RRPM reduces to about 99.5%. This RRPM will pretty much remain constant throughout the normal flight envelope (give or take a couple of %).

**Flight Idle is a condition when the throttles are fully forward and allow fully automatic engine governing. With the throttles in this state, the RRPM should remain constant whether on the ground or with a high pitch setting. Governors work very basically like this: they sense an increase or drop in RRPM and almost instantaneously increase or reduce the amount of fuel going in to the engines. RRPM slows down (because of applying pitch/drag) = more fuel to the engines = RRPM goes back to its original speed. The opposite occurs when they sense an increase in RRPM (when lowering the collective).

Here’s the official US Army’s description:

REDSTONE ARSENAL, Ala. — The “corona effect” is characterized by distinctive glowing rings along metal or fiberglass rotor blades operating in desert conditions.

The glowing rings are made up of numerous small sparks resulting from grains of sand striking a normally-operating rotor blade, meaning the corona effect can be seen only at night.

The corona effect has been seen from about a half mile away on a CH-47 Chinook hovering at about 1,700 feet, said Mike Hoffman, and that without the aid of night vision goggles.

17 August 2009

Sangin, Afghanistan

The roads are so littered with enemy bombs that nearly all transport and resupply to this base occurs by helicopter. The pilots roar through the darkness, swoop into small bases nestled in the saddle of enemy territory, and quickly rumble off into the night.

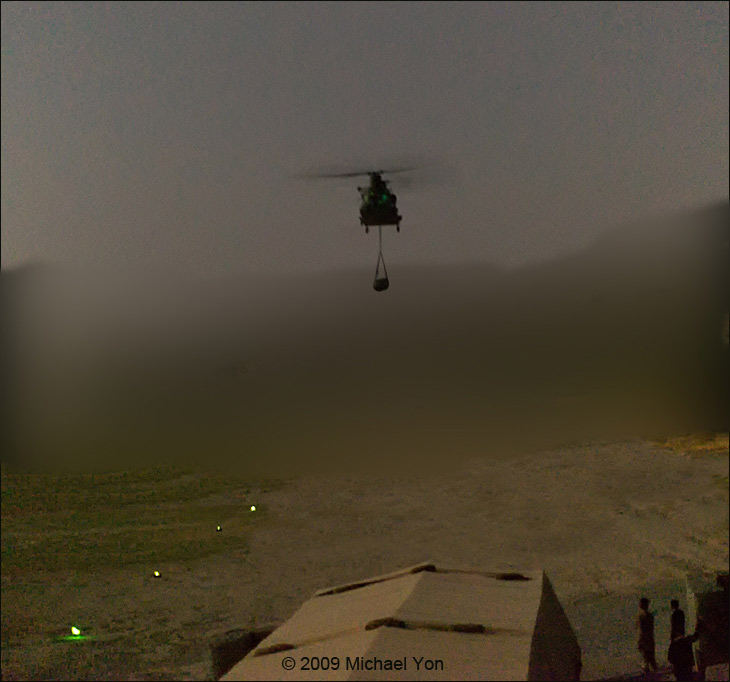

A CH-47 helicopter whirls in with a “sling load” of resupplies from Camp Bastion to FOB Jackson in Sangin.

The pilot comes in fast, to the dark landing zone, lighted only by “Cyalumes,” which Americans call “Chemlights.” The sensitive camera and finely engineered glass make the dark landing zone appear far lighter. The apparent brightness of the small Cyalumes provides reference.

A show begins as the helicopter descends under its halo.

The charged helicopter descends into its own dust storm.

Gently releasing the sling load.

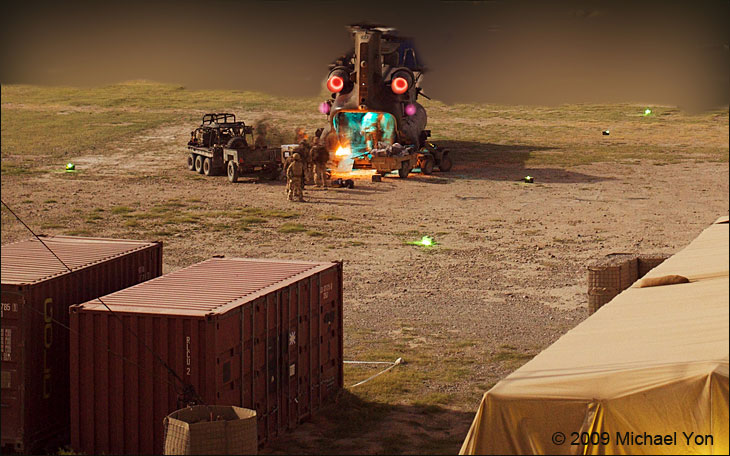

The pilot hovers away from the load, pivots and begins to land.

The dust storm ripples and flaps over the medical tents.

Heat causes the engines to glow orange.

Dust begins to clear even before landing. The helicopter, under its own halo, casts a moon shadow.

The halo often disappears when the helicopter ramp touches the ground. Again, the conditions are quite dark, but the excellent camera gear has tiger vision.

The British medical staff treats many wounded Afghans who often show up at the gate. In the photo above, Dr. Rhiannon Dart (right) observes as an Afghan patient is medically evacuated to the trauma center at Camp Bastion. The medics and Dr. Dart are especially respected for the risks they equally share here. The medical staff walks into combat just like the other soldiers—frequently side by side in close combat. Numerous times per week, their battlefield work, often under intense pressure in hot and filthy conditions, is the deciding factor on whether soldiers or civilians survive or die. I asked Dr. Dart if Afghan men have any reservations when being treated by a woman. She answered that when men are seriously wounded—which is about the only time she sees Afghans as patients—they don’t care if she is a man or a woman. During a mission last week, I saw an Afghan soldier walk by with a bandage on his hand. Dr. Dart stopped the soldier, asking him to remove the bandage. Contrary to harboring reservations, the soldier appeared relieved that she wanted—actually sort of politely demanded—to examine his injury.

The ramp lifts in preparation for takeoff and the halo begins to rematerialize before the helicopter lifts into the darkness and disappears. Soldiers call the medevac flights to Camp Bastion, “Nightingales” or “Nightingale flights.” Shortly after sunrise on the morning of 13 August, an element from this unit was ambushed nearby, killing three and wounding two others. Despite the immediate danger, the helicopter came straight onto the battlefield. After the initial ambush, and another successful ambush during the evacuation, the British soldiers did not return to base but continued with the mission. Later that evening they were twice ambushed again, sustaining more fatalities as two interpreters were killed. Soldiers asked me to go on that mission but I was busy assembling this dispatch. One of the killed soldiers, shortly before the mission, had looked over my shoulder as I selected the photos. Captain Mark Hale was killed while aiding a wounded soldier. Mark had particularly liked the next three images:

Night after night, helicopters keep coming. Last month a civilian resupply helicopter had tried to land at this exact spot but was shot down on final approach. Two children on the ground and all persons aboard were killed. The helicopter crews earn much respect.

Sometimes the halos appear like distant galaxies.

In motion, the halos spark, glitter and veritably crackle, but in still photos the halos appear more like intricate orbital bands.

Perhaps like the rings of Saturn.

The halos usually disappear as the rotors change pitch, dust diminishes and the ramp touches the ground. On some nights, on this very same landing zone, no halos form.

Note: By request of the British Army, a handful of these photos were slightly altered to obscure base security measures. The alterations are limited to minimal parts of several photos.

Note: By request of the British Army, a handful of these photos were slightly altered to obscure base security measures. The alterations are limited to minimal parts of several photos.

On another night, the helicopters return. The camera is jostled, accidentally creating a double image.

They keep coming.

A phenomenon in need of a name. Mark Hale had liked this image and the next.

I spent two weeks searching for a fitting handle but all attempts came to naught.

The halos are different every night. Some nights they are intense, other nights dim, but often there are no halos.

There are explosions and fighting every day and night.

Under the moon.

This time exposure shows where the pilot briefly hovered before dropping in.

Our casualties in this war reached an all-time peak in July 2009 and the heaviest fighting was here in Helmand Province. On 10 July, elsewhere in Helmand, some of America’s finest soldiers were hunting down Taliban.